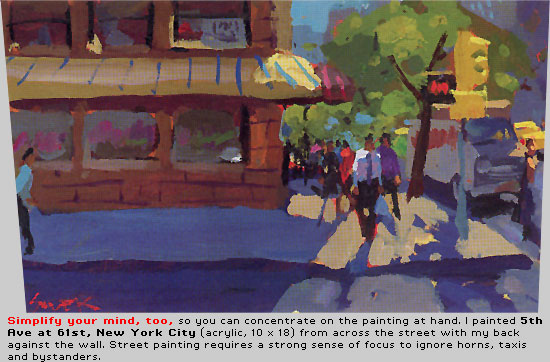

Charles Sovek revels in finding the aura, the intangibles, the mystery, and the character of the many cities he has painted during his travels. He searches for old neighborhoods, busy street corners and intriguing buildings, observing people, too, at each stop. "A city just lends itself to painting," Sovek says. "It has structure, form, shapes and figures, plus personality and spirit."

BDK: You're going to New York City for a painting trip. How do you decide what to paint? What's your plan of attack?

CS: I like to paint a small section of a city–a village or neighborhood that has character and personality. I like to find a small town or enchanting village within a city and really get to know it. Before I ever take out a brush, I'll hang out in a park or on a street corner and soak up the atmosphere. I believe my paintings are stronger when I'm in touch with the subject, as opposed to painting lots of sites I'm not familiar with.

If I was going to New York City to paint, I'd spend my time in Central Park or Greenwich Village. I wouldn't try to capture every landmark or site the tour book recommends.

BDK: Do you have a set itinerary when you arrive in a city, a list of sites you'd like to paint?

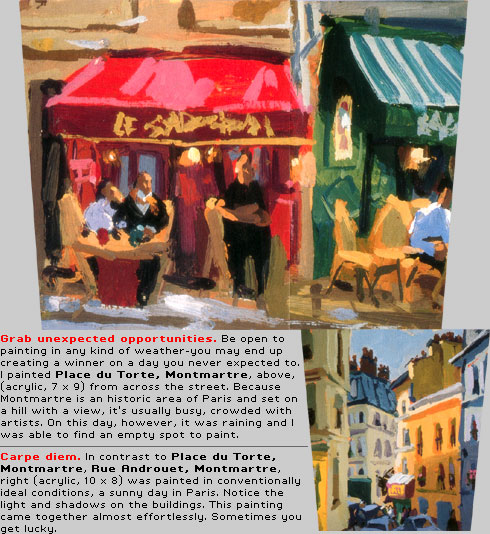

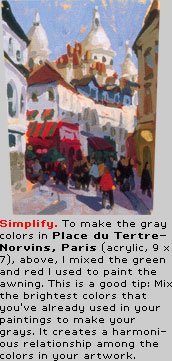

CS: No, I don't have a rigid itinerary but rather a flexible direction, and then I believe in letting things flow. I'll do some research ahead of time, and I have ideas of places to check out when I arrive in a city, but I like to walk around and just see what strikes me. I might spend a morning or afternoon browsing around to get a feel for things. Once you have ideas of what to paint,, you still have to be open to circumstance and playing thngs by ear. The last time I was in Paris, I was painting in Montmartre, and it was pouring down rain. Our group found a few shelters with awnings to keep dry. It turned out these shelters provided an amazing view of Paris–perfect for a painting. (See Place du Torte, Montmartre) I would never have thought to paint from this vantage point, but real life intrudes. If you're willing to go with the flow, sometimes it pays off. One of the worst things you can do is to have a strict itinerary or a rigid game plan because you'll shut off that internal compass.

BDK: How do you find the perfect scene to paint?

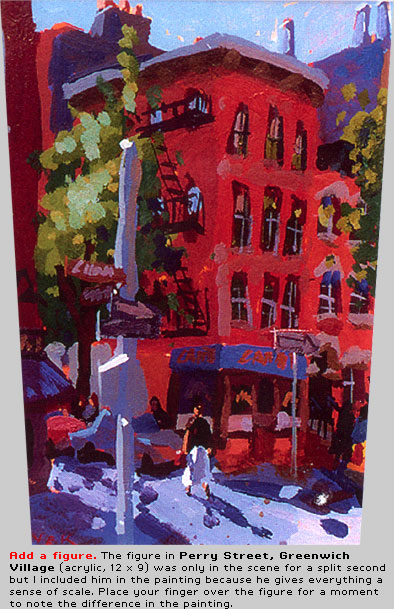

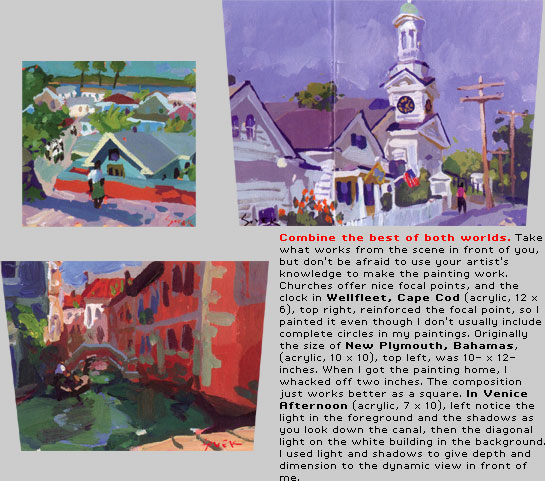

CS: Seldom do you come across the "perfect scene." Ninety-nine percent of the time, you'll have to eliminate a tree or shorten a building. I don't necessarily add things to a scene, but I do borrow. Let's say I'm painting a street and my point of view includes three trees, two cars and a figure. I look to my right and see a hot dog vendor, which would add just the right color note to my painting. So I borrow the vendor, who isn't really in my vision, and put him in my picture. Cézanne showed us how to do this. He worked from ten points of view, not just one.

CS: Seldom do you come across the "perfect scene." Ninety-nine percent of the time, you'll have to eliminate a tree or shorten a building. I don't necessarily add things to a scene, but I do borrow. Let's say I'm painting a street and my point of view includes three trees, two cars and a figure. I look to my right and see a hot dog vendor, which would add just the right color note to my painting. So I borrow the vendor, who isn't really in my vision, and put him in my picture. Cézanne showed us how to do this. He worked from ten points of view, not just one.

BDK: What part do people play in portraying a city?

CS: All my paintings include figures, and to me, the people play a big part in describing a city. Obviously, a New Yorker has quite a different look than a person in Dallas. A Parisian has a different appearance than a person in Venice. When I'm out and about in a city, I observe the crowds. I look for a pattern among the people–a flavor. For instance, no one wears denim in Paris, and in Venice everyone wears denim and scarves. I notice these generalizations and incorporate them into my artwork to enhance my portrayal of a city.

BDK: Once you've chosen a site, how do you decide what specifically to paint?

CS: You can take one of three approaches: You can paint a vista, a close-up, or a little of each. There's no magic formula to decide on the approach. You could do all three and see which outcome you like best.

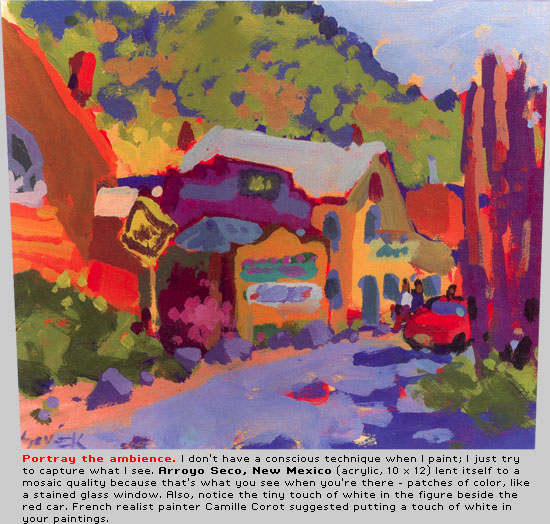

You just have to trust your gut. When you've painted for a number of years, a little inner compass tugs at you when you've got a good subject. French Impressionist Camille Pissarro calls it that sensation that tickles your imagination.

BDK: Do you like to paint the modern parts of a city, or the old?

CS: I gravitate toward the old sections or sites in a city because you tend to find more character and mystique. The old neighborhoods and buildings have charm, intrigue and history. The Fauvists, such as Henri Matisse, Andre Derain and Georges Braque, painted the old stuff, too, because it lends itself well to expressive brushstrokes.

BDK: Do you ever paint from reference sketches or photos?

CS: I like to work directly from life–firsthand. Confronting the real thing seems to be the best way I can breathe life into a picture. I enjoy painting outdoors because all the senses are active. I smell the flowers, hear the birds and the noise, and feel the wind. All these elements add to my experience and what I put on the canvas. Preliminary sketches and photographs leave me feeling locked into something, whereas I like the open dimension of painting from life–on the spot.

Also, I give myself a time limit for a painting, usually three hours, which keeps me focused and energetic. If I stopped and tried to start up again the next day, I would lose my groove. When traveling, I do two paintings a day: one in the morning and another in the afternoon, breaking in between for lunch.

I try not to get too caught up in the details of my subject. I get the spirit of a scene without getting out a ruler and making it perfectly proportioned. I boil things down to reach the essence of the subject. When I paint a car, I don't paint a Volvo or Mercedes, I paint a blocky shape that creates a sense of scale. I don't care if the taillights aren't in the exact right spots.

BDK: Any other advice?

CS: Always be ready, and trust your instincts. I once had a layover in Athens, on my way to the Greek Islands. I walked outside my hotel and there was a public park where I saw ladies with babushkas and black dresses. It screamed Greece. I had to paint the scene. I didn't plan it, but it was right there waiting for me. So don't have every little minute and every painting planned. Let it flow–be loose and flexible.

Charles' Tool Box

Sovek says, "I've seen masterpieces that were painted on a canvas propped against a rock with a fishing tackle box for supplies. Point is: Don't go overboard." Here's what Sovek carries with him.

Sovek says, "I've seen masterpieces that were painted on a canvas propped against a rock with a fishing tackle box for supplies. Point is: Don't go overboard." Here's what Sovek carries with him.

Easels – Full- or half-French easel and a pochade box with a tripod

Palette – For oils, use wood, Plexiglas or tear-off paper. For acrylics, use tear-off paper. For watercolors and gouache, use a white butcher tray or a plastic version, such as the John Pike palette.

Colors – Cool red, warm red, orange, warm yellow, cool yellow, green, blue, black and white

Brushes – For oils and acrylics, bring two each of No. 1, No. 3, No. 5 and No. 7 bristle flat brushes; a round or filbert and a small rigger for details. For watercolors and gouache, use one each of the best quality No. 3, No. 5 and No. 7 round sable brushes you can afford; a 1-inch flat sable or synthetic brush and a small rigger.

Palette knife – It's useful for all mediums. Get the kind with an inverted handle, not the more awkward model shaped like a table knife.

Painting surfaces – For oils, use canvas board, Masonite panels primed with gesso, or stretch canvas. For watercolors, use either cold- or hot-press papers no lighter than 140 lbs. For acrylics and gouache, use cold-press illustration board panel. For pastels, use pastel papers in various colors as long as the tone is lighter than a middle gray.

Miscellaneous – Paper towels or rags for cleaning, razor blade scraper for your palette, screw-on umbrella for your easel, pens, pencils, camera, film and bug spray