![]()

Articles

|

Turn On the Glittering Light of Impressionism: The Art of Frank Benson

By Charles Sovek The Artist's Magazine - October, 1989

Impressionist Frank Benson brought a fresh breeze of sparkling light and color to Boston's conservative exhibition halls and, along with his fellow artists, changed the course of American painting. Now, nearly a century after his sun-splashed canvases were first shown, the work of this talented American painter still evokes the admiration of art students and public alike. His depictions of rosy-cheeked young women, children on holiday, duck hunters prowling the Massachusetts wetlands and fishermen wading through sun-dappled streams capture not only the nostalgia of a bygone era but also a quality of light and color that's unmistakably Benson's.

A study of Benson's output reveals not only an impressionist in search of new solutions to picture making, but also a stubborn Yankee who refused to trade his love of structural solidity for a visual effect. Drawing upon the color innovations of the French impressionists, Benson and his band of likeminded contemporaries set out to challenge the inhibiting tonal approach then prevalent throughout Boston's artistic community, and legitimize the use of the natural effects of light and color as a valid way to paint. BACKGROUND AND INFLUENCES Born in Salem, Massachusetts in 1862, Frank Weston Benson began studying art in his late teens at the Boston Museum School. Upon completion, he traveled to Paris, furthering his studies at the Academie Julian and spending summers painting in Brittany. With a strong academic background and a newfound awareness of light and color, Benson returned to Boston in 1885, earning a living teaching at the Museum School. There, he settled down to fashion the raw material he gleaned from abroad into a technique distinctly his own, characterized by glittering light and color as well as solid volumes and draftsmanship. Within the next nine years, Benson's active role in the Boston artistic community led to his acceptance as a member of the "Ten." This elite group of plein-air painters included Childe Hassam, Edward Simmons, Willard Metcalf, J. Alden Weir, Robert Reid, Edmund Tarbell, Thomas Dewing, Joseph De Camp and John Twachtman, and provided Benson with a support group whose company he continued to enjoy and exhibit with for the rest of his career. Aside from a mural commission for the Library of Congress, Benson's artistic output falls into two general categories. The first - and the area in which he is now most famous-are his outdoor compositions of single figures or groups. The best of these works were done from about 1900 on. These usually depicted his attractive, goldenhaired daughters in flowing white dresses, basking under brilliant sunlight and silhouetted against verdant, colorful landscapes, bright blue skies and fleecy clouds. These paintings show the artist's fascination with light and color and are much more spontaneous than his earlier works. During this fertile period, Benson also painted portraits and still lifes. His portrait commissions were mostly of society figures, and in the mode of 18th-century aristocratic portraiture, many included women with children. The second category reflects Benson's involvement in sporting subjects, especially duck shooting. The popularity these paintings brought him enabled him to give up his 25-year teaching career to paint full time until his death in 1951 at the age of 89. WORKING PROCEDURE Preferring either a white or lightly toned canvas and using charcoal or a thin, neutral color, Benson began his paintings with a sketchy, yet well proportioned drawing. Usually working from life, he would then mass in the large patterns of light and dark with a thin oil wash and, as was the custom with most of the American impressionists, immediately begin to apply thick, opaque paint, filling in the large mosaic of broad patterns and colors that formed the basis of the effect he was trying to capture. Elaborating on his lay-in, Benson would then establish and develop the secondary passages of the subject, carefully noting both the color and value changes of a form.

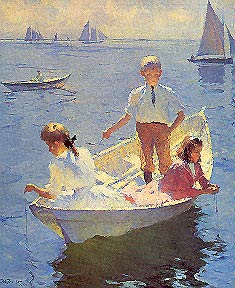

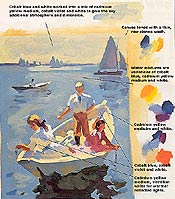

Last would come the final layer of strokes that would carry the painting to completion. Though considerable time may have been spent in finishing a work, Benson was careful to keep his brushwork crisp and incisive, avoiding any tendency to overly detail a piece. Like Monet, the artist refused to work on a sunstruck subject if the day turned overcast, choosing instead to wait for the particular effect to return. Because of the many time lapses, it's doubtful the artist developed his entire painting wet-into-wet. Close inspection of various works reveals numerous drybrush effects that could only be accomplished by painting over dry pigment. RAINBOW PALETTE Benson's early palette relied heavily on earth colors, using changes of value rather than changes of hue to solidify a form. Soon tiring of the limitations imposed by this academic approach, he began employing the more effervescent "rainbow" palette similar to the one pioneered by the French impressionists. Umbers, ochres and siennas were discarded in favor of more primary spectrum colors. No record exists of the actual hues Benson employed. Because of Monet's strong influence, however, it's safe to say he used a similar range of colors which included: chrome yellow (long since replaced by the more permanent cadmium yellow medium), lemon yellow, vermilion, cobalt violet, Prussian blue, cobalt blue, emerald green, viridian green and chrome green. Now free to explore the fall range of color inherent in his subject, Benson quickly became adept at such techniques as graying a color with a complement, juxtaposing warm and cool hues, and accenting shadows with pure color. Study the painting, Calm Morning (above) and notice how the artist splashed the warm yellow of the early morning sun into all the lightstruck passages of the composition. Even the blue of the water is tinged with traces of yellow. To emphasize this effect, observe how the shadows lean toward blue-purple, effectively complementing the warm areas of light. Notice also Benson's use of colorful darks. The bow in the hair of the foreground figure, the sock of the standing boy and the shadowed hair of the figure to the right could all have been painted with black or burnt umber but Benson instead chose to liven up these areas with darks mixed from reds, oranges and blues. JUGGLING TONE AND COLOR One of the biggest challenges that face impressionists of any school is how to handle the light-to-dark gradations of tone needed to render the solidity of a form without dissipating the purity of the colors. Dark-value hues such as blue, purple and green present no problem because the addition of white can actually increase their brilliance. Colors high on the value scale such as yellow, orange and red, however, are easily muddied when attempts are made to darken them. Black and earth tones in particular can easily destroy the intensity of such colors. But the French impressionists discovered that by lightening the overall tonality of a painting, you decrease the degree to which a color needs to be darkened. This means a yellow object need now be only deepened a value or two to provide a suitable range of modeling tones. This is one reason many impressionists preferred painting white or light-toned subjects rather than dark motifs. Monet solved this problem by minimizing any modeling values and concentrated instead on recording only the various color changes that met his eye. Eventually his canvases became nothing more than a myriad of colorful brushstrokes, dissolving even the faintest hint of tonal modeling into a shimmering effect of light.

Reluctant to sacrifice form for color, Benson seldom let go of his feeling for the volumes of a form, and, while wholeheartedly accepting the color theories of French impressionism, he found his own way to maintain the weight and solidity of a subject. DIFFERENT STROKES It's interesting to study the ways various painters apply pigment to a surface. Sargent painted in swaggering dashes, Cézanne used a twill pattern, while Seurat employed a series of dots. Most artists interested in light usually apply the paint thickly and employ consistently shaped brushstrokes throughout the composition. This equalizes the surface texture of a painting and forces the viewer to take in the entire effect rather than any one part

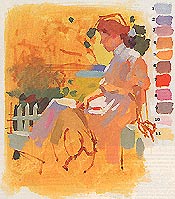

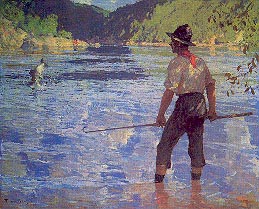

Benson, like Monet, Pissarro and Sisley, preferred to build his painting up with a fabric of small, daub-like strokes. This allowed him to incorporate dozens of color changes into any given area. Study Benson's treatment of the water in Salmon Fishing (below) and notice how each separate stroke records a different color note. Observe also the handling of the dress in Eleanor (above) and study how the small swatches of color act like the facets of a diamond, each taking on a different hue. LIVELY REFLECTED LIGHTS Another hallmark of Benson's impressionistic style is his lively handling of light. Capitalizing on the dazzling brightness of New England's coastal light, the artist began backlighting his models to make use of color-charged reflected lights. This not only heightens the feeling of brilliant sunlight but also adds glowing luminosity to the shadows. Study the handling of the dress in Eleanor and notice the phantasmagoria of reflected color. To show how effectively Benson's color juxtapositions work, focus on the shoulder and observe how blue the fabric appears. Now isolate the knee and notice that it looks violet, whereas the underplanes of the waist and lower torso appear orange. Studying the dress as a whole, however, it magically takes on the glow of a pinkish-white fabric veiled in pulsating shadow.

Another example of Benson's color wizardry is the sun-drenched figures and boat in Calm Morning (above). Here again, the artist's choice of backlighting enables him to use reflected light as a modeling tone in the shadows. Notice how the warmth of the sun is splashed into the cooler shadow areas and how inventively the artist has reflected subtle shades of warm yellows into the cooler darks. This effect is particularly noticeable in the shadows of the white dress and shirt of the standing and seated figures, the underplanes of the standing figure's face and the shadowed interior of the boat. It's this kind of sensitive observation that gives Benson's paintings such a remarkable quality of existence. COMPOSITION, MOOD AND EFFECT With the exception of commissioned portraits, most of Benson's figure compositions tend to be candid in layout. Like casual snapshots, these works have an intimacy and relaxed quality that make them his most successful works. The brushwork is fresh and the mood is friendly with almost a holiday atmosphere. Nothing appears forced or overstudied.

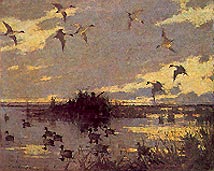

In contrast to these are the artist's more contrived hunting and fishing subjects. Here the mood is definitely more dramatic and monumental, and rather than the figures taking precedence, the landscape prevails. These paintings also tend to be more tonal, with color used to subordinate rather than accentuate an effect. Pintails Decoyed (above), for example, is essentially a study in pale gray, yellow and brown, and it appears nearly monochromatic when compared to Eleanor or Calm Morning. Benson's restrained palette, however, does fit the subject, and it's no wonder he received such wide public acclaim for this series. It would be interesting to imagine, however, what mood Pintails Decoyed might have taken on if painted with the same assertive color used in his figurative pieces. Frank Benson was one of the first painters of his time to "Americanize" impressionism and capture the light of New England in all its raw beauty. His work will always have a place in the art history of our culture and will continue to be a source of learning and inspiration to artists of all schools and expression. |

||||||||||||||

|

Home | Gallery | Workshops | Lessons from the Easel | Speaking of Art | Biography | Feedback Copyright © 2016 - All Rights Reserved - Charles Sovek |